Edward William Pritchard: Gone?

Content warning: Contains descriptions of violence.

In the depths of the Mitchell Library lies three boxes, filled with untouched documents from the Glasgow Photographic Association of the mid to late 1800s - at least they were untouched - until now.

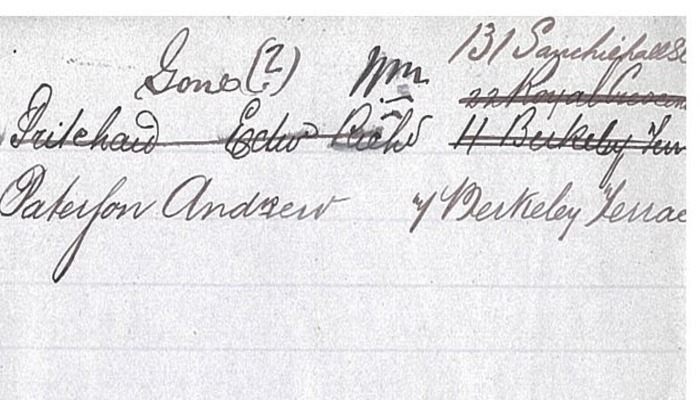

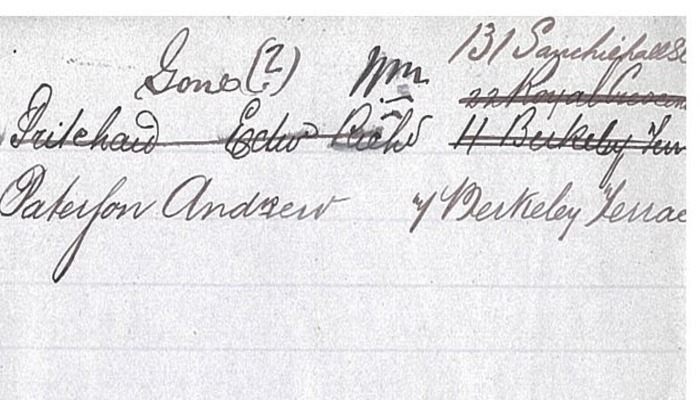

One of the highlights of the collection is a small book, filled with the names and addresses of members of the Association. On one page, the name Edward William Pritchard has been crossed out, and above it, written: “Gone?” (see below left MS250.220 Notebook of members and their addresses).

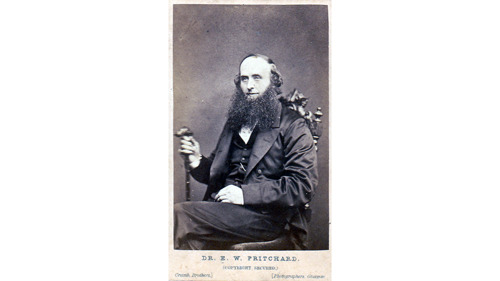

Edward William Pritchard, known by one man as the “prettiest liar” he had ever met, was many things - a liar, a navy officer, a doctor, a philanderer, a blackmailer, an aspiring photographer, and eventually, a murderer.

PLACEHOLDER

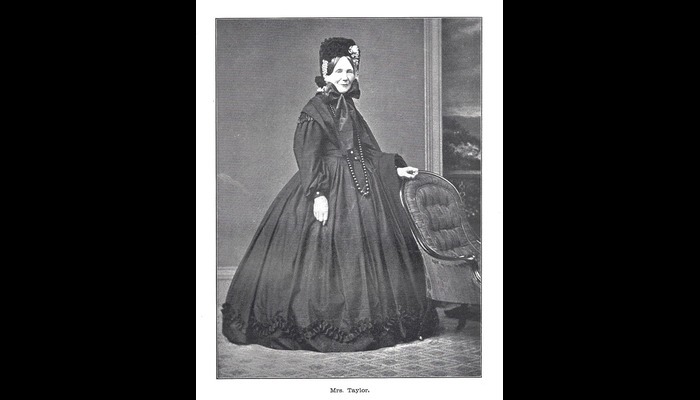

Born into a naval family, Pritchard followed the footsteps of his family and became a medical navy officer. He eventually met and married his wife, Mary Jane Taylor, the daughter of a wealthy merchant and the niece of a well-respected navy surgeon. With the support of his in-laws, he moved with Mary Jane to Hunmanby, where the Taylors had opened up a practice for him.

In Humanby, he began to develop quite a reputation. It was rumoured that he would seduce and sleep with his young female patients and blackmail them into keeping it quiet. He tried his best to keep up appearances in Hunmanby - he joined the Freemasons and bought a degree from a German university. Despite this, it seemed that the entire town knew what he was up to. At the urging of his in-laws, he went on a trip abroad and moved to Glasgow after with his wife and five children. By the time he left Hunmanby, he was regarded as a “politely impudent, and singularly untruthful” man in “discredit and debt” - according to an issue of the Sheffield Telegraph in 1865.

The Taylors paid for many things in Pritchard’s life and supported him throughout his time in Hunmanby and Glasgow. They paid for his house after his old one had mysteriously caught fire with his maid inside, they established his practice in Hunmanby, helped his adventures abroad in Egypt, and supported him during his move to Glasgow. Somehow, though, he seemed to squander away all of his money, even the money so kindly loaned to him by his mother-in-law. When she died, she left money for her daughter, in today’s money, nearly a quarter of a million pounds that would soon be Pritchard’s.

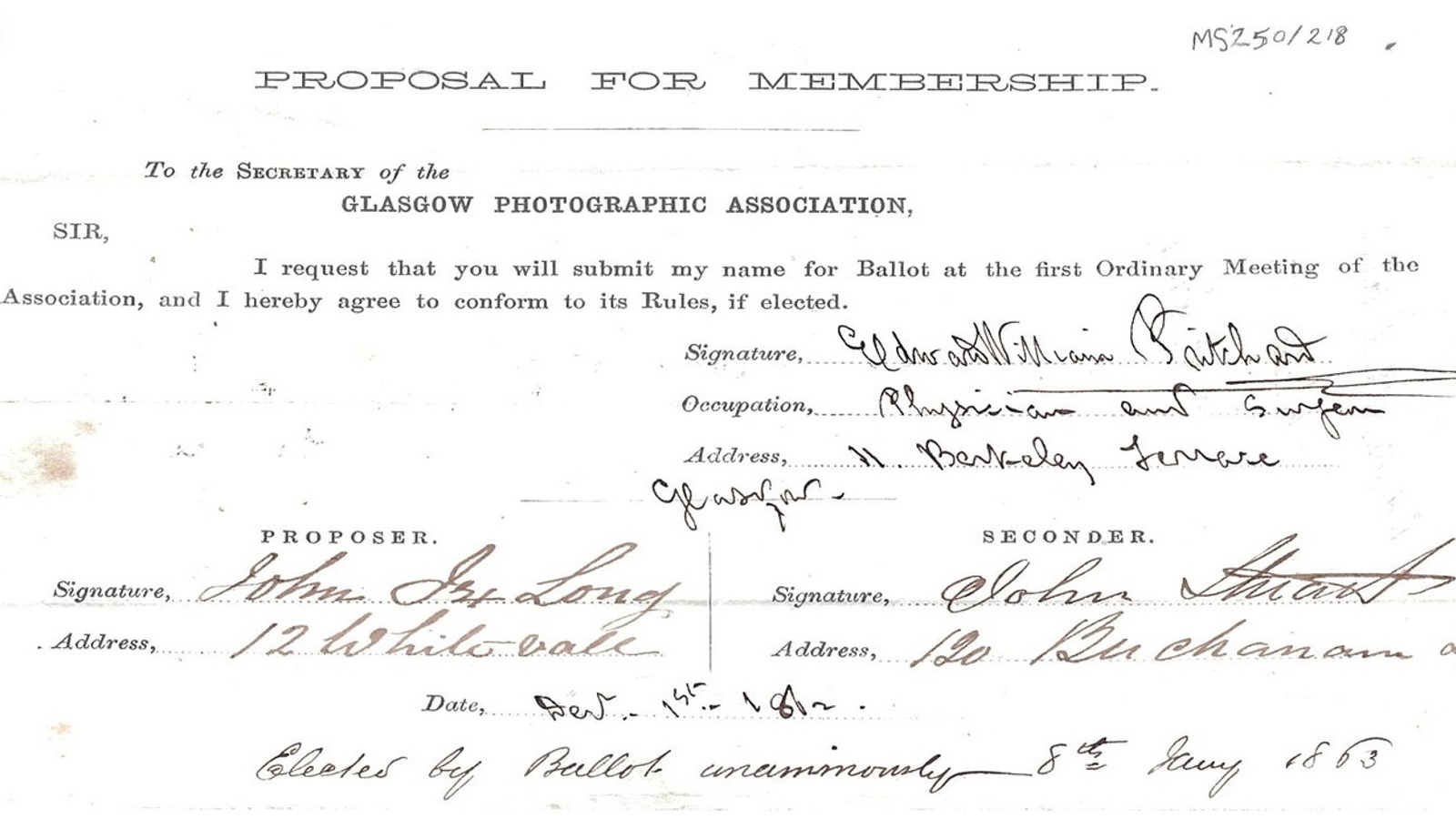

It was no surprise to anyone who knew of Pritchard’s reputation that he had continued to be a treacherous philanderer in Glasgow - though he also continued his efforts to hide it. He became a Free Mason in Glasgow as well, rose to the top of the Glasgow Athenaeum (now the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland), and even applied to be part of the Glasgow Photographic Association. John Stuart and John Jex Long proposed his membership, the latter of whom would later be the president of the Association in 1865 - the year Pritchard was hanged.

In January of 1863, Pritchard was unanimously voted into the Association, and later that year, he would commit the first of three murders.

In the Glasgow Photographic Association’s book of members next to Pritchard’s name is three addresses, two crossed out, including 11 Berkeley Terrace, which had lit ablaze in 1863. In the ashes, they found the burnt body of the pregnant Elizabeth McGirn, one of the Pritchard family’s servants and one of Mr. Pritchard’s many lovers. It is suspected that, while he was never convicted of it, Pritchard impregnated her, convinced her to get an abortion administered by him, and when he went to do so, he chloroformed her instead and burned her alive.

Pritchard got away with the murder at the time but drew many suspicions when he made an insurance claim on his home and jewelry he claimed to be missing, clearly trying to make some money out of the murder. His insurance claim was approved, but he received only a small portion of the money he could have got.

His next address at Royal Crescent survived his murderous wrath, but there he had begun an affair with Mary MacLeod, another one of his servants. Soon she would also be pregnant, but this time Mr. Pritchard promised to marry this servant should his wife die. The family and Mary then moved to Sauchiehall Street, where Pritchard would buy and administer poison to his wife and mother-in-law Mrs Taylor.

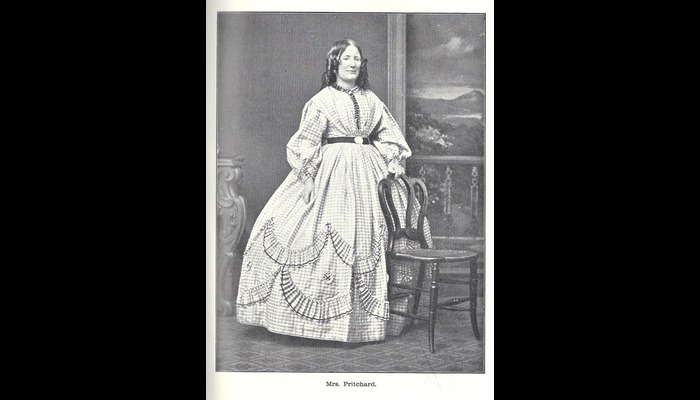

After discovering her husband and her servant kissing in her own home, Mary Jane mysteriously fell ill. When she visited her family in Edinburgh for Christmas, she recovered. But when she was back home, in the care of her husband, her health took a turn for the worse. Her mother came to take care of her, but Mrs. Taylor ended up eating some of Mrs. Pritchard’s food

and also became sick. So did the two servants who tasted Mrs. Pritchard’s food before it was served to her, but unlike Mrs. Taylor, they survived.

Mrs. Taylor died in February of 1865.

Mary Jane asked for doctor after doctor to visit her: her cousin - who diagnosed her with an irritated stomach; professor of Medicine at the University of Glasgow; Dr. Gardiner - who diagnosed her with hysteria, and Dr. Paterson - who was present the night she died.

Mary Jane tried to tell Dr. Paterson that she had been vomiting all day, but Dr. Pritchard told both her and the doctor that she had been hallucinating and that she had been well all day. She died that night in March of 1865, and in his diary, Dr. Pritchard wrote:

‘Died here at 1 a.m., Mary Jane, my own beloved wife, aged 38 years – no

torment surrounded her bedside.’

Dr. Pritchard asked Dr. Paterson to write up the death certificate, but Paterson refused since he had not been observing the two women to know well enough what the cause of death was. Pritchard wrote it instead, writing the cause of death for his mother-in-law as paralysis and apoplexy and his wife’s as gastric fever.

At the funeral, Pritchard asked the coffin to be opened again so he could kiss his dead wife one more time. Not soon after, the authorities received an anonymous letter- thought to be penned by Dr. Paterson - tipping them off to the murders. The bodies were exhumed, their cause of death was ruled to be poison, and Pritchard was tried for murder. He was found guilty and was hung in Glasgow Green. He was the last person to be publicly executed in Glasgow, and over one hundred thousand people stood and watched as he was punished for his crimes.

So yes, Pritchard was gone - and he spent nearly all of his life lying, seducing, and killing, unbeknownst to the people of Glasgow.

Find out more about the Glasgow Photographic Association here.

To make an appointment to see the collection, please contact us.

Further Reading

About the author

Anne Van Hoose is a fourth year Digital Media and Information Studies student at University of Glasgow. She is also a graphic designer, and used to give tours at the Hunterian Museum. Her interests include true crime, making board games, and baking. She spent her 2024 summer volunteering with the Mitchell Library, and hopes that you will spend some of your free time volunteering with your local galleries, libraries, archives, and museums!