Bruce Report - Times Past

In partnership with the Glasgow Times, our archivists are exploring Glasgow's fascinating history. This week, Michael Gallagher writes about the First Planning Report of the Glasgow Corporation, also known as the Bruce Report.

Imagine you were tasked with making Glasgow a better city. Would you decide to destroy some of its most beautiful, historic buildings and start again?

One intriguing document we hold is the First Planning Report of the Glasgow Corporation, dated March 1945. Don’t be fooled by the bland name: within it is a dramatic vision of a new Glasgow which, if it was implemented, would be unrecognisable to the city we know today.

The plan was drawn up by Robert Bruce, the Master of Works and City Engineer. The aim was to transform Glasgow into a “healthy and beautiful city” over a period of fifty years. It covered five key areas: transport, housing, industry, open spaces and the redevelopment of “blighted areas”.

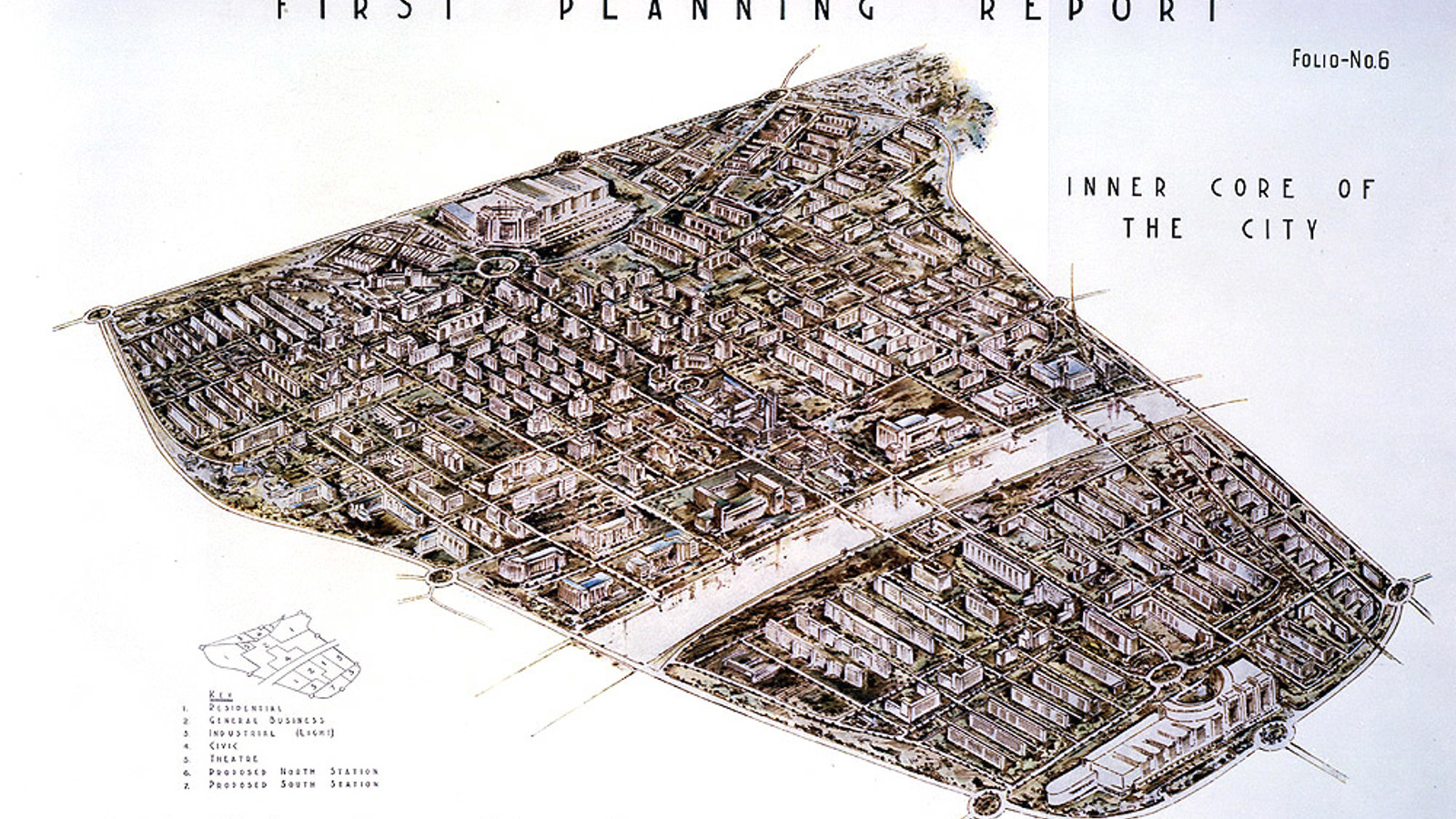

Bruce wanted to “secure order out of disorder”. He proposed to destroy almost all of the historic city centre, including iconic buildings like Glasgow School of Art, the City Chambers and our home, the Mitchell Library. These would be replaced by a new central core, created along modernist principles, with an emphasis on clean lines and no “unnecessary” architectural detail. Think of a stereotypical city in the old Soviet Bloc and you come close to the aesthetic.

The new city centre would comprise functional zones for different purposes: commercial, residential, civic and entertainment. Heavy industry would be removed from the city centre. As would the residents of its houses, who were to be rehomed in new high-density schemes on the edge of the city but within its boundaries. Everything was to be connected by an efficient transport infrastructure, including a new ring road system.

Bruce’s plan sounds shocking today, but must be viewed in the context of the time. The aftermath of the Second World War was a time for optimism and the desire for a better world. Urban planners felt that they could create a new social order through “creative destruction”. Bruce believed his proposals would lead to lower infant mortality, higher life expectancy, more facilities for leisure and more time to use them, a cleaner atmosphere, cleaner homes and better community spirit in better planned areas. All noble aims driven by idealism and good intentions, even if the method was somewhat extreme!

The plan was abandoned in 1949 but some of Bruce’s ideas lived on. Particularly in the construction of high-rise flats across the city and changes to the road network, like the M8. It is a sad irony that Bruce himself died in a car crash in 1956.

Archives are special as they allow us to see the workings of history and the thought process behind it. In this case, we get a glimpse of what Glasgow might have looked like in another reality. Sometimes, the raw materials of the past can reveal just as much as the events that actually took place.