Louis Edward Campbell (1851 - 1894) - The Mitchell Library's Black Benefactor

We were pleased to chat to researcher Morag Cross, recently, about this fascinating history of Mitchell Library donor Louis Campbell (1851 – 1894). We are sharing this as part of Black History Month. A full version of the article was published in History Scotland – May / June, 2019.

Born in Martinique

Louis Campbell was born on St Pierre, on Martinique, in 1851, the son of Glaswegian Alexander Campbell, a West India merchant ‘of large means’, and ‘a coloured French mother’, whose name is unrecorded. A French colony, Martinique had only abolished slavery in 1848. After spending his first 10 years on Martinique, his father sent Louis to Scotland to attend school. Alexander remained in Martinique to run the firm A & J Campbell with his brother John.

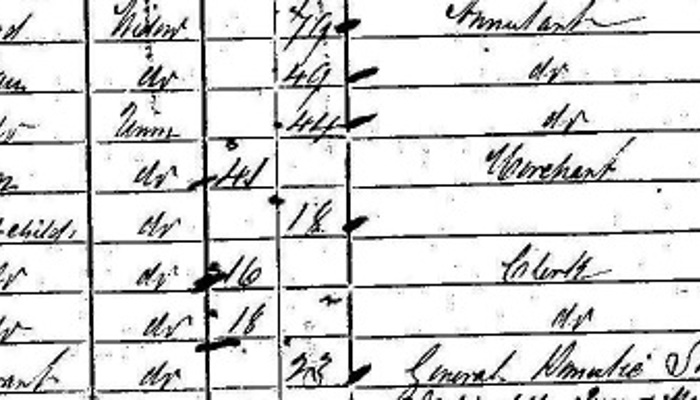

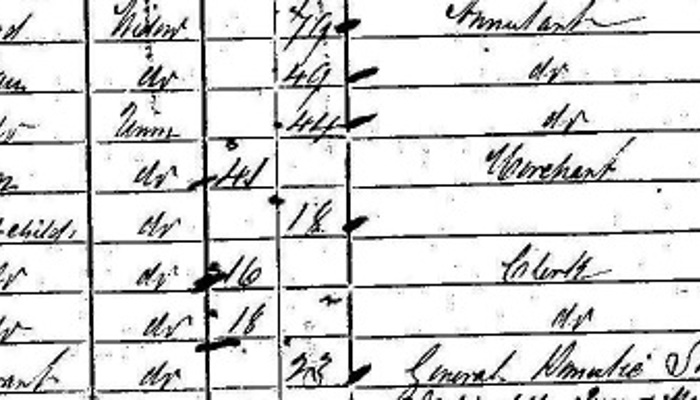

Louis is listed on the 1861 & 1871 censuses as a grandchild, which shows that he was accepted as part of the family. He was working as a clerk, a common occupation for a young, educated man of Glasgow.

In 1878 Louis’ grandmother Agnes was paid 77,700 francs as her share of the Martinique company, which was probably used to purchase 3 Eton Terrace (now 45 Oakfield Avenue), which was desgined by renowned Scottish architect, Alexander "Greek" Thomson. Agnes died in 1876, leaving Louis, his aunt Ann and a servant in the house. By 1881 Louis was working as an analytical chemist. Ann died in 1892, leaving shares and savings worth £3,556. She was buried in the Necropolis, beside her parents.

Research information

Family strife

Morag Cross writes:

“Ann’s death seems to have unleashed long-simmering family resentments. Louis asserted that his uncle, John, had not fully paid over £10,000 as Ann’s share of the Martinique firm. Louis was counter-sued by the elderly John, alleging that Louis was unrelated to the Campbells, and Ann had been paid in full. In a separate case, Ann’s sister and her sons claimed that they were owed £900 by Louis. It is worth noting that nothing is written about any personal hostility towards Louis’s ethnicity. Although such racism may have played a part in the court proceedings, this must remain speculative, as specific evidence isn’t recorded.”

Tragic death

Louis lost the court case, which dragged on for two years. He rented out 3 Eton Terrace, and moved to Springburn. After the case was concluded, he was ordered to pay his uncle’s court expenses. He left Glasgow completely, to a boarding house in Edinburgh.

Tragically, Louis was found dead at 37 Forrester Road, Edinburgh, having ‘suicidally swallowed a quantity of carbolic acid’, due to ‘chronic cerebral disease’.

The Mitchell Library paid for an elaborate Celtic-revival cross to be erected as a gravestone in Newington Cemetery. The inscription on the base reads:

In memory of Louis Edward Campbell Died 25 May 1894: Aged 42 years; Erected by the Libraries Committee...of Glasgow as his residuary legatees

Celtic-revival cross in Newington Cemetery

In memory of Louis Edward Campbell Died 25 May 1894: Aged 42 years; Erected by the Libraries Committee...of Glasgow as his residuary legatees.

Morag writes:

“This phrase [chronic cerebral disease] may be a (very vague) euphemism, or could just indicate the modern phrase, ‘while the balance of his mind was disturbed’. Louis’ motives can only be guessed at. He presumably felt emotionally vulnerable after the humiliating judicial verdict. Although his extended family do not seem to have made an issue of either his birth-status or his colour, it was mentioned as a ‘negative’ by his Uncle John.”

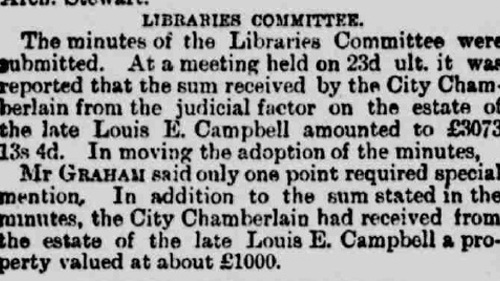

Louis’ brief will was found in his rooms at Forrester Road: ‘I leave to the Mitchell Library of Glasgow the whole of my effects’. This will was written before any of the family disagreements. This article from the Glasgow Herald on 2nd August 1895 describes the legacy left by Louis to the City of Glasgow.

As Morag Cross writes:

“Louis Campbell’s biography challenges cursory or over-simplified modern assumptions that overt racism was the default attitude towards ethnic minorities in Victorian Glasgow. His story is more nuanced, indicating both that the narrative of each person of colour is unique, and that many more such biographies remain to be uncovered.”

His story is that of one of many donors to the Mitchell Library, and we are delighted that it has been uncovered.