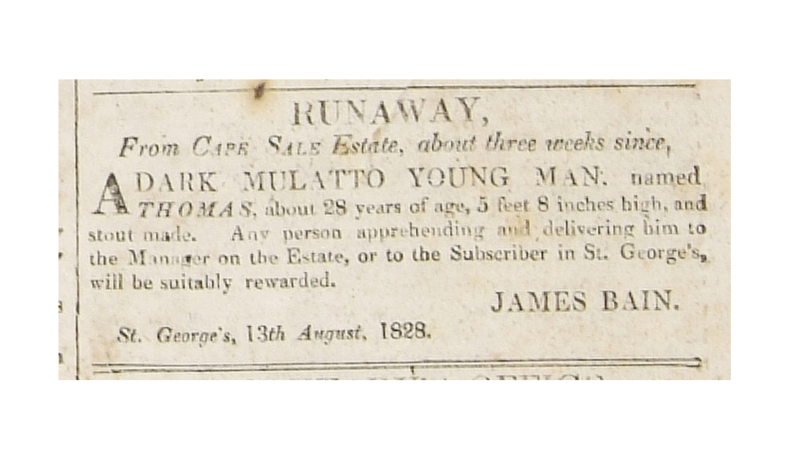

The advert reads: ‘RUNAWAY From Cape Sale Estate, about three weeks since, A DARK MULATTO YOUNG MAN named THOMAS, about 28 years of age, 5 feet 8 inches high, and stout made. Any person apprehending and delivering him to the Manager on the Estate, or to the Subscriber in St. George’s, will be suitably rewarded. JAMES BAIN. St George’s, 13th August, 1828.’

James Bain was a Scottish planter and owner of the Cape Sale and Belmont plantations in Grenada, as well as a property in the main town of St George’s. Lists of the enslaved people on his estates, compiled between 1817 and 1834, show that Bain owned more than 200 people, although this number would fluctuate a little. When enslaved women on Bain’s estates gave birth the number would rise, as their new born became Bain’s property. Likewise, when Bain’s enslaved people died, often from exhaustion, fever, disease or in some cases suicide, numbers would decrease.

Whether Thomas managed to avoid recapture we cannot be sure, but we know that James Bain retired to Elmbank Place in Glasgow to enjoy the wealth he had obtained by exploiting and enslaving people in Grenada.

Katinka Stentoft Dalglish,

Curator of Archaeology