Degas and the ‘black world’ – The Artist’s links to Slavery and Racism

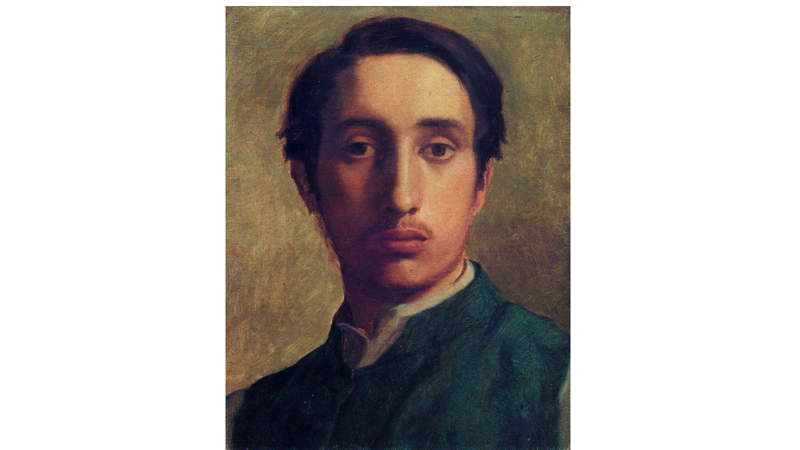

Self-Portrait, Edgar Degas, about 1857

Oil on canvas, Private Collection

Image in the public domain, via wikiart.org

3rd February 2025

Edgar Degas is an artist well represented in Glasgow Life Museums, with 24 pastels, paintings and sculptures by the French artist in the collection. From May to September 2024, Degas was the focus of the first major temporary exhibition at the recently refurbished Burrell Collection, Discovering Degas – Collecting in the Time of William Burrell.

Degas is one of history’s best-known visual artists, and a founding member of the Impressionists. He exhibited in all but one of their eight groundbreaking exhibitions, the first of which opened 150 years ago, in 1874. The artist’s unusual perspectives, distinctly modern subjects and experimental use of oil pastel define him as a pioneering and progressive artist, and his paintings of the ballet are instantly recognisable the world over. What is less familiar about Degas is his connection with the world of slavery and racism.

Degas was the only French Impressionist to spend a period of time in the USA. From October 1872 to March 1873, he stayed in New Orleans, Louisiana, living with his uncle Michel Musson and family, in a household that included three female cousins, six young children and Degas’s youngest brother, René de Gas. While in the ‘Crescent City’, Degas wrote five letters back to his friends in Paris, detailing the difficulty he had painting his fidgety young relatives, his almost immediate desire to return to his beloved Paris, and his interest in the everyday sights of New Orleans, particularly the Black population, described by Degas as the ‘black world’.

Despite this professed interest in the city, in the approximately 16 paintings and drawings he made whilst there, Degas shied away from depicting much of New Orleans. His failing eyesight could not tolerate the bright Louisiana sunlight, and so Degas was restricted to a domestic, claustrophobic indoor setting. Scenes include his cousins nursing their children, arranging flowers or even receiving a pedicure. One fascinating exception to this rule can be seen in the artist’s representation of another domestic scene, Courtyard of a House (New Orleans, sketch), 1873. Set on the edge of the grand Musson house on the wealthy Esplanade Avenue, Degas pictures four of his cousins, along with a hastily drawn Black servant, positioned low down within the composition, her covered head and part of a grey dress just visible to the left of the scene. Exhibited at the second Impressionist exhibition, 1876, this sketch is a glimpse of the world Degas occupied during those five long months. A time when, cooped up indoors, every day he would have encountered at least six Black servants, tending to the vast family’s needs. Why he didn’t depict Black servants – or indeed Black people of any occupation – again during his time in New Orleans, or at a closer range, is an intriguing question, especially considering that the artist was fascinated by the working classes throughout his career.

Although Degas did not picture much of New Orleans whilst living there, the five letters he wrote back to friends do provide an idea of his attitudes towards the ‘black world’. Degas enthuses throughout these letters, particularly describing the vivid colours and stark distinctions he saw in the clothing and different skin colours of the locals, and yet his admiration is rooted in racism. He writes, ‘I like nothing better than … the contrast between the lively hum and bustle of the offices with this immense black animal force…’ (Letter to Lorenz Fröhlich, New Orleans, 27 November 1872).

The word ‘animal’, used to describe the Black population, and set against the industrious white world of the offices, is obviously dehumanising. Further discriminatory descriptions can be found throughout the letters.

It is a little-known fact that Degas was related to a person of colour. The artist’s mother, Célestine Musson (1815–47), was born in New Orleans, and her maternal uncle, Vincent Rillieux, had a longstanding relationship with a free woman of colour named Constance Vivant. Several of Degas’s mother’s cousins, therefore, were mixed race. One of these cousins was especially eminent – Norbert Rillieux (1806–94, the inventor of the revolutionary vacuum pan, used in sugar processing that produced particularly fine, white sugar.

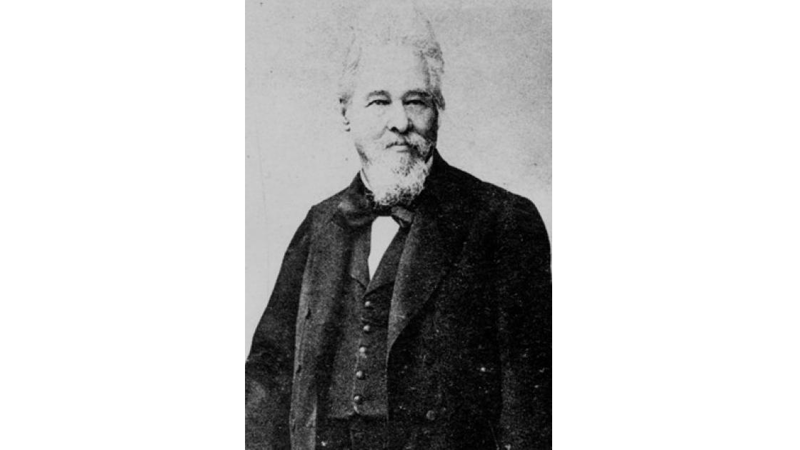

Norbert Rillieux (1806–94)

Norbert Rillieux (1806–94), a mixed-race scientist, was Degas’s second cousin.

Degas visited New Orleans not ten years after the American Civil War finally brought about the end of slavery, during the incredibly unstable Reconstruction period. The Black population, which in 1870 constituted roughly 25% of New Orleans’ population, owned a meagre 1.3% of the city’s property. Furthermore, unemployment was rife, with roughly one fifth of the Black male population in New Orleans unemployed.

Louisiana society was carefully divided into different social classes, dependent upon an individual’s shade of skin, or percentage of African descent. Norbert’s life as a mixed-race individual with a Black mother and white, European father would have been very different from that of the Black servant pictured on the step of the Musson household. Degas’s familial connection with the ‘black world’ was to a particular, elevated part of that society. Norbert was highly educated – he studied in Paris, and spent the last few decades of his life in the French capital, passing away in 1894. Nevertheless, despite some privileges, Black people even from the higher end of society still faced demeaning restrictions and prejudices, for example his parents’ union – degradingly called ‘miscegenation’ at the time – was regarded as abhorrent by a large section of society, particularly influential newspapers. Mixed-race couples like Norbert’s parents could not legally marry, and they would not be able to do so in Louisiana until 1972.

It is unclear whether Degas even knew that he had a Black relative. Due to his deep interest in science and technology, the artist would likely have been aware of the existence of Norbert Rillieux, but would he have known that this man was his second cousin, his mother’s cousin’s son? The familial link was only discovered by scholars in the 1990s, and it is entirely possible that Degas would have been unaware of this connection. It is unlikely to have been something of which his right-leaning American family would have been proud.

The Musson family, headed by Degas’s uncle Michel, were closely entangled with cotton, an industry that had relied on the labour of enslaved people. New Orleans was the largest US export site for cotton leaving the South. Michel owned a cotton factoring firm, while Degas’s brothers Achille and René de Gas ran a cotton office nearby. Degas wrote that he was proud of his brothers’ business, and pictured the offices in two impressive canvases made just before his return to Paris. In the larger of the two, A Cotton Office in New Orleans, 1873, the artist pictures key members of his family at work, including Michel, Achille and René de Gas.

Michel Musson, René de Gas and William Bell (son-in-law to Michel) were heavily involved with the White League. This paramilitary terrorist organisation, founded in 1874, used violence to curtail the freedoms of Black people. Unlike the infamous Ku Klux Klan, members of the White League did not hide their identities and were freely identifiable in their many high-ranking positions across society. Degas’s close relatives took lead positions – Michel Musson was so close with the organisation’s leader that in 1873 he was asked to preside over a 5,000-strong riot of white men, which resulted in 43 dead and 79 wounded. While Degas was living under the same roof, his male relatives were part of a milieu that would create this violent white-supremacist group. Although, unlike his brothers, Degas was not actively involved with the cotton trade, his existence was closely bound to the trade, and indeed to slavery. Both sides of his family had enslaved people, and his mother’s dowry had been provided by the sale of an enslaved girl from New Orleans.

When we celebrate an artist through research, or an exhibition such as the Burrell Collection’s Discovering Degas – Collecting in the Time of William Burrell, we focus on an individual’s brilliance and skill – which Degas had in abundance. However, it is important to acknowledge areas associated with artists that are not a cause for celebration. Degas’s connection with New Orleans offers an important insight into a world of prejudice and enforced labour, with which the artist’s family were closely associated, and which Degas viewed at first hand.

Horse Tied to a Tree, Edgar Degas, about 1873–80

Oil on panel, The Burrell Collection, accession number 35.240

This small painting was once owned by Degas’s brother, René de Gas, who ran a cotton business and was involved with the racist organisation the White League.

Image © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

Further Reading

Christopher Benfey, Degas in New Orleans: Encounters in the Creole World of Kate Chopin and George Washington Cable, Knopf, 1997

John W Blassingame, Black New Orleans 1860–1880, University of Chicago Press, 2007

Marilyn R Brown, ‘Miss La La’s’ teeth: further reflections on Degas and ‘race’, in Perspectives on Degas, ed. Kathryn Brown, Routledge, 2018

Gail Feigenbaum and Jean Sutherland Boggs, Degas in New Orleans: A French Impressionist in America (exhibition catalogue), Rizzoli, 1999

Denise Murrell, Posing Modernity – The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today, Yale, 2018