Gustavus Brown’s Runaway Slave

'Run away'

Newspaper advert

Edinburgh Evening Courant, 9-13 February 1727, page 4

14th August 2018

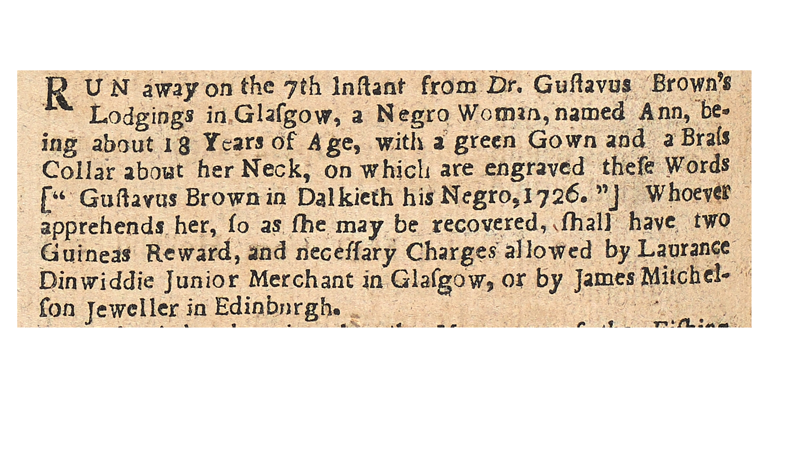

In February 1727 Dr Gustavus Brown placed this advertisement in The Edinburgh Evening Courant:

RUN away on the 7th Instant from Dr. Gustavus Brown’s Lodgings in Glasgow, a Negro Woman, named Ann, being about 18 Years of Age, with a green Gown and a Brass Collar about her Neck, on which are engraved these Words [“Gustavus Brown in Dalkieth his Negro, 1726.”] Whoever apprehends her, so as she may be recovered, shall have two Guineas Reward, and necessary Charges allowed by Laurance Dinwiddie Junior Merchant in Glasgow, or by James Mitchelson, Jeweller in Edinburgh.

Brown had trained in Edinburgh as a doctor before emigrating to Maryland where he married, established a successful practice, and became a wealthy and successful doctor and tobacco planter. His Maryland-born son, also named Gustavus, was likewise training in medicine at Edinburgh, and would go on to serve in the Continental Army and then attend his friend George Washington during his final illness. Brown Senior owned lands in both Scotland and Maryland, and he owned people too: at his death Brown senior left his lands and ‘all [forty-five] negroes, hogs, horses, sheep, [and] cattle’ for the use of his wife until her death, at which time Brown Junior would inherit his father’s property.

Thirty-five years earlier Brown Senior had brought Ann with him on a visit to Scotland. Ann was unusual in being forced to wear a collar. Brown’s Maryland home was named Rich Hill, close to Port Tobacco, so ‘Dalkeith’ referred to his Scottish property, and this brass collar was quite likely made, fitted and engraved in Scotland. The brass collar did not bear Ann’s name, and the wording inscribed upon it instead identified her owner, affirming Brown’s wealth and status while demeaning the unfortunate young wearer as nameless property. Why had Brown had this metal collar fitted around Ann’s neck? Had she escaped before, and was this designed to discourage further attempts and to mark her clearly as enslaved and as Brown’s property? Or was the collar an ostentatious display of wealth and power by the local boy-made-good, an eye-catching affirmation that Brown was sufficiently successful to own Ann and others like her? We cannot know, just as we do not know what became of Ann, just eighteen years old and very far from family and community in Maryland when she ran away. Did she find refuge, or was she recaptured, and eventually taken back to Maryland by Brown? Ann’s name did not appear on the list of forty-five enslaved people owned by Brown when his possessions were inventoried thirty-six years later, unless she was Nan, one of the oldest of Brown’s enslaved people, and valued at £35. If Nan was a diminutive of Ann and this was the same person who had once run away in Scotland, what stories of Scotland did she have for her children and grandchildren? Or perhaps she had been sold to another Maryland planter, or perhaps she had died young as was true of so many enslaved plantation workers. Or maybe she had escaped and lived the rest of her life in Britain?

As is the case with most advertisements for runaway slaves we may never know the whole story. And as usual, we have only the words and description penned by an angry master and no idea of Ann’s eventual fate. Yet this advertisement and others like it allow us to glimpse the enslaved people brought to Scotland and imagine their experiences while here.

Professor Simon P. Newman

History, School of Humanities, University of Glasgow